|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

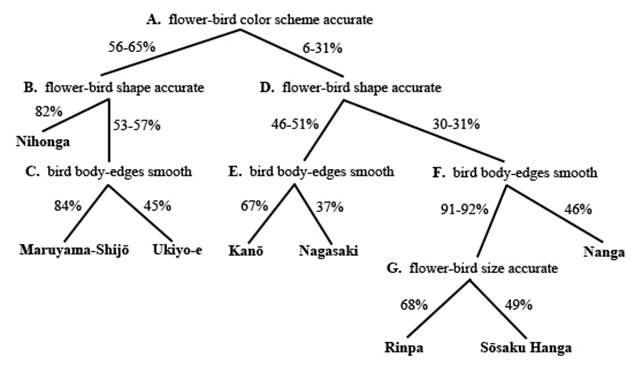

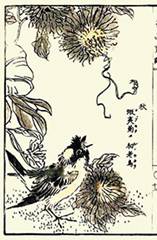

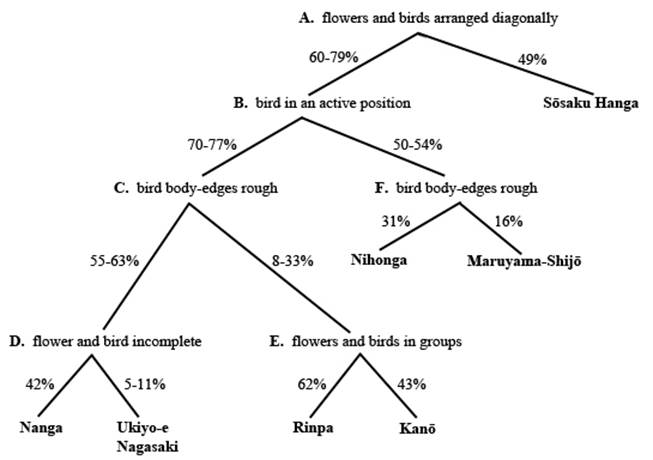

Historians of Japanese art recognize a number of stylistic schools based on differences in the approach taken by artists to depict their subject matter. Artists of eight of these schools drew flower-bird pictures. These eight schools are commonly called Nihonga, Maruyama-Shijō, Ukiyo-e, Kanō, Nagasaki, Nanga, Rinpa, and Sōsaku Hanga. The origin and meaning of these names are explained in the descriptions of individual schools which follow. Stylistic boundaries between these schools are relatively soft because

artists frequently borrowed and adapted techniques of other schools. As a

result, differences between schools are typically quantitative rather than

qualitative. In other words, one school may use a particular technique more

often than another but the use of that technique is not restricted to a

single school. The fact that differences are mainly quantitative makes it

more challenging to distinguish between schools. Figure 3.1 Four-step classification of eight Japanese stylistic schools (bold type) based on differences in the percentage of pictures showing features related to accuracy.

In this classification scheme the school whose pictures show greatest accuracy (i.e., Nihonga) appears on the far left of Figure 3.1. Proceeding from left to right the level of accuracy gets progressive lower until the least accurate school (i.e., Nanga school) is reached on the far right.

At each

step in the classification procedure the eight schools are divided into

smaller and smaller groups based on the percentage of their pictures which

show accuracy for a particular measure.

3.3 Revealing Flower and Bird Spirit Traditional

far-eastern artists aimed to reveal the inner spirit of their subjects (e.g.,

flowers and birds) rather than their external form (Rowland, 1954). Inner

spirit is typically revealed by showing the subjects of a picture either in

action or interacting in some way. A number of artistic techniques can be

used to show, or suggest, action and interaction including the following five

(Lauer, 1979):

Figure 3.2. Examples of five techniques used to help reveal flower and bird spirit.

All five techniques were used by the eight Japanese artistic schools that drew flower-bird pictures. Some techniques were used more often than others and schools differed in their use of a particular technique. The eight schools are classified and distinguished based on these differences in Figure 3.3. At each step in the classification procedure the eight schools are divided into smaller and smaller groups based on the percentage of their pictures that used a particular technique to reveal flower and bird spirit.

Figure 3.3 Four-step classification of eight Japanese stylistic schools (bold type) based on differences in the percentage of pictures showing features related to flower-bird spirit.

In this classification scheme the school with the highest percentage of pictures using these techniques (i.e., Nanga school) appears on the far left of Figure 3.3. Proceeding from left to right the use of these techniques decreases until the Sōsaku Hanga school is reached on the far right. At point A. the eight schools are divided into two groups based

on the percentage of their pictures which show flowers and birds arranged

diagonally (60-77% of pictures for each of seven schools versus 49% for the

Sōsaku Hanga school). This classification has both similarities and differences with the previous

classification of the eight schools based on their accuracy of flower-bird

depiction (Figure 3.1).

In the early 1600s military leaders of the Tokugawa clan defeated their rivals and set up a new national government. To help maintain their control on power, government leaders promoted the Chinese philosophy of Confucianism which emphasized loyalty and moral behaviour by their subjects. In addition, they associated themselves with Chinese art and culture which had long been admired by the Japanese (Guth, 1996). Members of the Kanō family, appointed by the government as official state artists, were commissioned to produce paintings with Chinese themes, including flower-bird pictures. For the latter Kanō artists adopted the style of the Che School of Chinese painting (Impey, 1982).

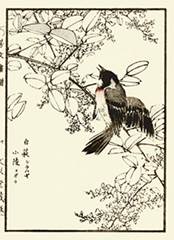

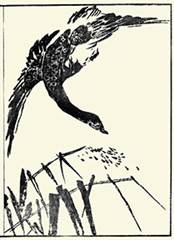

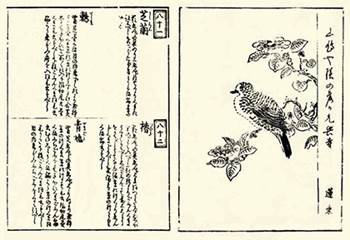

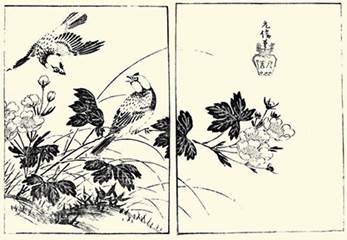

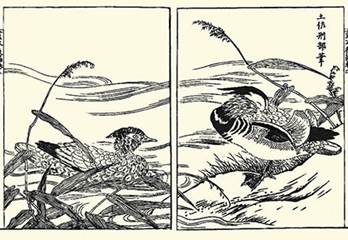

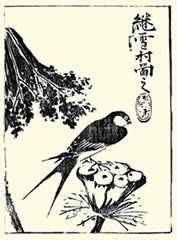

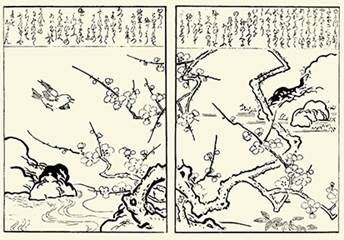

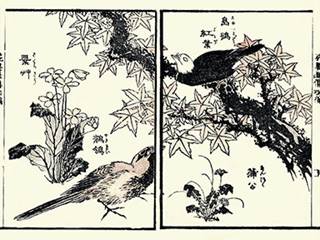

Some of the artists who were Kanō-trained or influenced published woodblock-printed books about Chinese-style painting. The audience for these books was mainly members of the cultured elite, military and government officials who wished to improve themselves culturally (Gerhart, 1999). Learning and cultural improvement were two additional Confucian principles promoted by government leaders. Painting books were of two types, the first containing sample pictures plus written instruction and the second containing examples of works by famous artists. Notable contributors to books with written instructions were Morikuni Tachibana who published a series of six books between 1720 and 1749 and Morinori Sekichūshi whose 1729 book included one hundred pictures based on paintings of Kanō Tan’yū and Kanō Tsunenobu. Morikuni’s pictures were black-and-white line drawings of flowers and birds, typically one species of each as in Figure 3.4. Little or no background was included and subjects were drawn with a medium degree of accuracy. Accompanying text commented on characteristics of the subjects important for their depiction. Morinori’s pictures shared these stylistic features although the shapes of flowers and birds were usually less accurate. Figure 3.5 by Morinori illustrates two compositional features borrowed from Chinese flower-bird painters; namely, a branch with flowers emerging from the picture’s edge (i.e., broken-branch technique) and subjects positioned asymmetrically either in one corner or on one side as in this case (i.e., one-corner technique). Chinese painters used these techniques to help communicate the vastness of nature and the universe by forcing the viewer to complete the plant’s outline in his mind, thereby extending the boundary of the picture outwards, and by including lots of empty space (i.e., the universe) (Boger, 1964).

Many books showing works by famous artists were published, mostly in the eighteenth century (Table 3.1). Not surprisingly, these books focused mainly on Kanō artists.

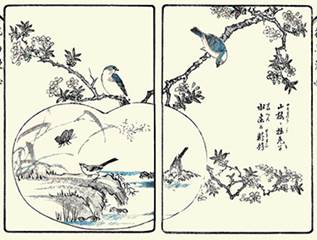

To illustrate the range of stylistic variation evident in these books, six examples chosen from pictures included in two books by Shumboku Ōoka (1720, 1750) are shown in Figure 3.6. All pictures were black-and-white line drawings. Flower and bird subjects were drawn with varying degrees of accuracy but none were true to life. Stylistic differences among schools appear to be minimal, partly because woodblock printing of the time could not replicate important details of brush stroke and color in the original paintings and partly because the paintings were all copied by an artist trained in the use of a single style.

Figure 3.6. Six examples of pictures included in two painting books by Shumboku Ōoka (1720, 1750). The name of the painting school is bolded.

Full color was first used for woodblock-printed pictures in the 1760s and books by the last two authors listed in Table 3.1 included pictures in color. Dairō Ishikawa (1802) presented a series of sketches by Tan’yū Kanō (Figure 3.7) while Gesssai Fukui (1894-6) reproduced paintings by Tsunenobu Kanō (Figure 3.8). A black-and-white version of the painting by Tsunenobu Kanō, copied by Morinori Sekichūshi in 1729 (Figures 3.9), illustrates the remarkable change in woodblock printing technology that occurred during the period of its use for painting books.

Figures 3.8 and 3.9. Hardy begonia (Begonia grandis), wire grass (Eleusine indica) and winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) painted by Tsunenobu Kanō and copied by Gessai Fukui (1896) on the left and by Morinori Sekichūshi (1729) on the right.

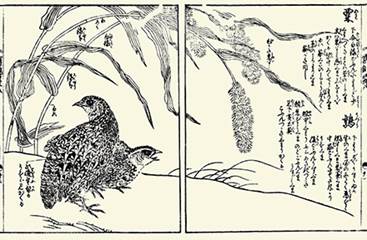

Some artists who were Kanō-trained or influenced illustrated encyclopedias that were published to facilitate learning and cultural improvement by the educated segment of Japanese society. Confucian philosophy championed the correct use of words, including the names of other living things, so encyclopedias usually contained a volume about plants and another about birds. While the focus of the bird volume was, of course, birds some pictures also included flowers as part of the background. (i.e., a flower-bird picture). The publication date and author of encyclopedias with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.2.

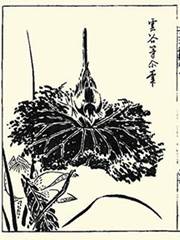

Two examples of encyclopedia pictures, one by Moronobu Hishikawa (Figure 3.10) and the other by Ryōan Terashima (Figure 3.11), are sufficient to illustrate their stylistic features. A black-and-white line drawing was used to show the subject’s basic shape. Surprisingly little surface detail was included and even the shape was often not entirely correct. Most pictures were relatively small, similar in size to that by Ryōan. Each picture was accompanied by a written description of the subject. Even with this written description it was likely difficult for readers to match the flowers and birds depicted with those seen outdoors because the quality of pictures was so poor.

Some of these pictures were redrawn and published in the late nineteenth century (Table 3.3). The original accompanying text was eliminated and partial color was added in some cases. Even with partial color it would still be difficult for readers to match real flowers and birds with those depicted.

Woodblock-printed pictures of flowers and birds were drawn first by artists who were Kanō-trained or influenced, starting in the 1680s. These pictures were included in books published to inform readers either about the flower-birds themselves (i.e., encyclopedias) or about techniques used to paint them (i.e., painting books). The audience for these books was members of Japanese society who wished to improve themselves culturally. Of the pictures examined for this analysis, almost all (94%) were black-and-white line drawings. The sparing use of color (6%) reflects the state of woodblock printing technology at the time when most pictures were published (i.e., 1680s to 1760s). Only about half (46%) of the pictures showed flower and bird shapes accurately. Artists were following the Chinese practice of de-emphasizing external form in favor of capturing the inner spirit of the subject. To help reveal inner spirit, birds were often shown in an active position (70% of pictures) and flower-bird subjects were arranged diagonally (66% of pictures). Other features of Chinese flower-bird painting were also used, including asymmetric positioning of subjects (i.e., one-corner technique) and showing plant parts emerging from the edge of the picture (i.e., broken-branch technique). The Chinese style was followed largely because it was promoted by government leaders of the time.

3.5 Style 2 - Ukiyo-e School 浮世絵派 When military leaders of the Tokugawa clan established a new national government in the early 1600s they adopted the Confucian four-class system as the basis for social order. Rulers and government officials were the top class, followed in turn by farmers, craftsmen and merchants. Ironically, those at the bottom of this social hierarchy often had more disposable income than those immediately above and many townsmen (i.e., craftsmen, merchants) used it to pursue a life of pleasure (Jenkins, 1993). Art work favored by townsmen was given the name Ukiyo-e which means pictures (e) of the floating (i.e., transient) world (Ukiyo). Some townsmen used the transience of life as an excuse for pursuing a life of sensory pleasure. Pictures of flowers and birds likely appealed to townsmen for four reasons. First, brightly colored flowers and birds were a source of sensory pleasure. Second, exotic birds and flowers were both novel and entertaining. Third, many flowers and birds were symbolically associated with human feelings, including pleasure. Fourth, flower-bird pictures were admired by the cultured ruling class and ownership of such pictures implied cultural sophistication (Hockley, 2003). Flower-bird pictures drawn by Ukiyo-e artists were used in four different ways; namely, wall decoration, art instruction, poetry illustration, and nature appreciation. Each of these uses is described, in turn, below.

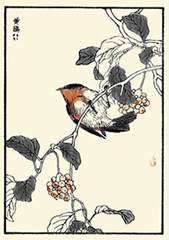

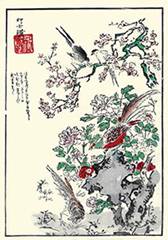

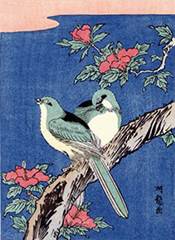

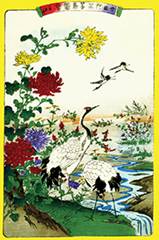

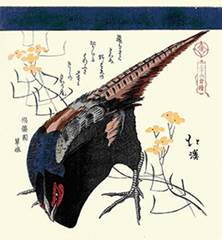

Starting in the early 1700s, printed flower-bird pictures were sold individually as inexpensive wall decorations (Narazaki, 1970). Four examples are given in Figure 3.12. The major axis of these decorative pictures was usually vertical, copying that of the more expensive scroll paintings. Flowers and birds were typically outlined in black and within the outlines color was applied. Initially only a few colors were used but by the late 1700s most pictures were multi-colored. Color was applied evenly giving the picture a flat, two-dimensional appearance. Rich, bright colors were preferred, especially after 1850 when synthetic chemical pigments from Europe became widely available. Colors chosen by the artist for flowers and birds were not entirely accurate, especially after 1850, suggesting that visual appeal was more important than accuracy. A picture’s sensual appeal could be further heightened by choosing either a flower or bird subject commonly associated with a human feeling. This was the case for 96% of Ukiyo-e decorative pictures included in this analysis. To help the viewer make an association, key features of flower-bird color and shape were shown but subjects were rarely drawn true to life. Ukiyo-e artists were more concerned with revealing the subject’s inner spirit than its external appearance (Hillier, 1960). Inner spirit was revealed by showing the bird in an active position (Figure 3.12 a,c,d) or with rough body-edges (Figure 3.12 a,c) or arranged diagonally with flowers (Figure 3.12 b,c).

Figure 3.12. Four Ukiyo-e flower-bird pictures used for wall decoration at different times.

Ukiyo-e artists who drew decorative flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.3. Only a few drew flower-bird pictures in the eighteenth century with Koryūsai Isoda being the most notable. During the following century many more drew flower-bird pictures especially members of the Utagawa family. Hiroshige Utagawa was the most important of these artists, producing hundreds of different designs. The output of all other artists was relatively modest by comparison.

Images of flowers and birds appeared on a wide range of consumer goods including fans, textiles, dishes, and boxes (Stern, 1976). Ukiyo-e artists provided ideas and models for this imagery in art instruction books. These books usually included human figures as well, often drawn in a humorous, entertaining way. Judging from the large number of books published (Table 3.4), they were very popular. Most were published in the nineteenth century with Hokusai Katsushika and his followers being the most important contributors.

Table 3.4. Publication date and author of Ukiyo-e art instruction books. Book titles are given in Chapter 4 under the authors’ names.

Images in these books were usually small, black and white line-drawings with color highlights (Figure 3.13). Detail was kept to a minimum consistent with the role of the image as a simple model. Accuracy was also sacrificed. The small size of each image meant that more than one could be presented on a single page. In some cases images even overlapped (Figure 3.13c).

Figure 3.13. Examples of flower-bird images from three Ukiyo-e art instruction books.

Between the early 1700s and mid-1800s composing and reading poetry were popular cultural activities (Mirviss and Carpenter, 1995). Published poems were often accompanied by pictures drawn by Ukiyo-e artists to further enhance the mood or theme of the poems. Some of these pictures featured flowers and birds. Four examples are given in Figure 3.14. Initially pictures were black and white line-drawings but by the late 1700s most were multi-colored. Other stylistic features were similar to those of decorative pictures described above. Most poems were either kyōka (Figure 3.14a,b,c) or haikai (Figure 3.1.4d). Kyōka is a 31-syllable poem presented in 5-lines of 5, 7, 5, 7 and 7 syllables. It parodied traditional Japanese court verse (i.e., waka) through humorous word play. Haikai is a 17-syllable poem presented in 3-lines of 5, 7 and 5 syllables. The poem merely suggested a certain mood or season and left it to readers to complete the meaning for themselves. It typically contained a season word, called kigo in Japanese, which could be the name of a flower or bird associated symbolically with that season. This illustrated poetry was published either in books (Figure 3.14a,b) or as individual prints. Some prints were rectangular (Figure 3.14c) while others were nearly square (Figure 3.14d). The nearly square format, called surimono, was often used as a greeting card or present for friends to celebrate the New Year and return of spring. The rectangular format was more suitable for display and some were likely used as wall decorations. Figure 3.14. Four examples of poetry illustration by Ukiyo-e artists.

Ukiyo-e artists who illustrated poetry with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.5. Utamaro Kitagawa is the most notable among those using the book format. His work was much admired, as it is today (Meech-Pekarik, 1981). The greatest number of flower-bird surimono were published by Hokusai Katsushika and his followers while Hiroshige Utagawa and his successor Hiroshige II published the most rectangular prints with a poem inscribed.

Some books published by Ukiyo-e artists included pictures of only flowers and birds (Table 3.6). Presumably these flower-bird books were intended for people with a special interest in nature. The earliest of these books, by Masayoshi Kitao (1789), focused on birds imported from China. Subsequent books included a mixture of exotic (65%) and native (35%) birds and flowers.

Table 3.6. Publication date and author of Ukiyo-e flower-bird books. Book titles are given in Chapter 4 under the authors’ names.

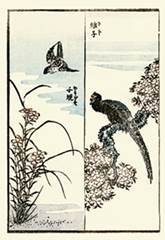

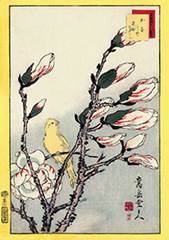

Books by Shigemasa Kitao (1805, 1827) and Sūgakudō Nakayama (1859) established a style that was followed by later artists. A picture from each of these two books is given in Figure 3.15. Flowers and birds were shown in full color but colors were not entirely accurate in most cases. Pictures published after 1850 often featured bright colors (e.g., yellow in Figure 3.15b) which was made possible by the importation of new chemical pigments from Europe. Shapes of flowers and birds were not always true to life as artists sacrificed accuracy to help reveal a subject’s inner spirit. Birds were often shown in an active, but somewhat unnatural, pose (Figure 3.15a) or with rough body-edges (Figure 3.15b). Flower size and shape were sometimes exaggerated for effect (Figure 3.15b). These inaccuracies reduced the usefulness of these books as identification guides.

Figure 3.15. Pictures from two flower-bird books published by Ukiyo-e artists.

In the early 1600s government leaders of the Tokugawa clan created a social hierarchy with themselves at the top and townsmen (i.e., craftsmen and merchants) at the bottom. While leaders had power townsmen had money which they spent on entertainment, including art. This art was called Ukiyo-e which means floating (or transient) world pictures, referring to the transient life of sensual pleasure pursued by some townsmen. The format, subject and style of Ukiyo-e art were similar to Kanō-style art in some respects and different in others. Kanō-style art was commissioned by government leaders while Ukiyo-e art was purchased largely by townsmen. Kanō-influenced artists illustrated encyclopedias with separate volumes for flowers and birds while Ukiyo-e artists illustrated books featuring both flowers and birds. Ukiyo-e books were less instructive, giving flower and bird names but no accompanying text as did encyclopedias. The absence of text allowed pictures to be larger which increased their visual appeal. Both Kanō-influenced and Ukiyo-e artists published books for art instruction but their intended audience was different. Kanō-influenced artists catered to the educated, upper class with pictures of paintings by famous Chinese and Japanese artists. Ukiyo-e artists provided simple flower-bird models for use by craftsmen who decorated consumer goods. Poetry was popular with all classes but townsmen parodied the poetry favored by the elite. Ukiyo-e artists added pictures to poems favored by townsmen and these poem-pictures were used both as greeting cards and as presents for friends. Ukiyo-e artists also drew many flower-bird pictures without poems inscribed. They were sold individually as inexpensive wall decorations, similar to the use of Kanō-painted scrolls by the elite. Ukiyo-e pictures almost always included a flower or bird that was symbolically associated with a human feeling or season of the year (i.e., 96% of pictures included in this analysis). Kanō-influenced pictures were only slightly less symbolic (92%). Kanō-influenced artists favored Chinese subject matter which included some flowers and birds not native to Japan. Ukiyo-e art featured even more exotic species (i.e., 115 species for Ukiyo-e pictures versus 76 species for Kanō-influenced pictures included in this analysis). Many of these exotic species would have been both novel and entertaining to townsmen. The flower-bird pictures drawn by Kanō-influenced artists were mostly black and white line drawings. Their use of black and white instead of color reflected the state of woodblock printing technology at the time. Most Ukiyo-e artists worked later when advances in printing technology made it possible to make multi-colored pictures. Ukiyo-e artists continued to use black to outline flowers and birds and then often filled these outlines with color. Only a few colors were used for flower-bird images which were intended only to provide ideas for craftsmen decorating consumer goods. Pictures produced for all other purposes, including wall decoration, poetry illustration and nature appreciation were largely multi-colored. Artists who worked after 1850 had the widest range of color available to them due to the importation of synthetic chemical pigments from Europe. Particularly bright colors were chosen then to maximize the visual appeal of pictures to purchasers wanting visual stimulation. Regardless of the number of colors used, they were applied evenly to create a two-dimensional picture. The use of uniformly-applied color is an important characteristic of Ukiyo-e art (Bell, 2004). Kanō-influenced artists followed the eastern tradition of attempting to reveal a subject’s inner spirit instead of its external appearance. Ukiyo-e artists continued this practice. Shapes of flowers and birds were drawn accurately on only 53% of pictures included in this analysis versus 46% for pictures drawn by Kanō-influenced artists. Compared to Kanō-influenced artists (K), Ukiyo-e artists (U) made even greater use of techniques to reveal a subject’s spirit; namely, birds shown in an active position (75% U versus 70% K), rough bird body-edges (55% U versus 33% K), and birds arranged diagonally with flowers (79% U versus 66% K). Spirited subjects would be particularly appealing to townsmen who sought lively entertainment to fill their spare time. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Chapter 3 – Styles 3-5 or Back to Guides

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||